Welcome to Vera Monstera's first guest post. Have we got a freefall for you! It is my great pleasure to introduce my friend John Eckert, a writer who is no slouch movement-wise. Fun fact: when he dances for joy, his knees give the illusion of being able to move 360 degrees, rather than the plain old hinge joints the rest of us have. This kind of wizardly craftsmanship moves through his writing, taking readers on a ride. Today’s jaunt is the art of the fall. Few human movements are more comedic, tragic or breathtaking. Before I drop out of frame and let John take the floor, please feel free to subscribe and share your thoughts. Every time you like a thing, writers get their wings.

Find songs from this essay on the Spotify Playlist.

John Eckert is the author of Decommissioned Cyborg Drinking Song, Solebury Mountain, and other poems. He and his screenwriting partner, Marlene Koury, wrote The Legend of Blaze Foley, Stacy’s Thing, and The Breakmakers. His book These Mirror Eyes: A Divine Comedy in the Songs of Elliott Smith (Pipersville Pheasant Press)1 is coming out in 2025.

Elliott Smith and the Pratfall: The Movement of Falling

By John Eckert

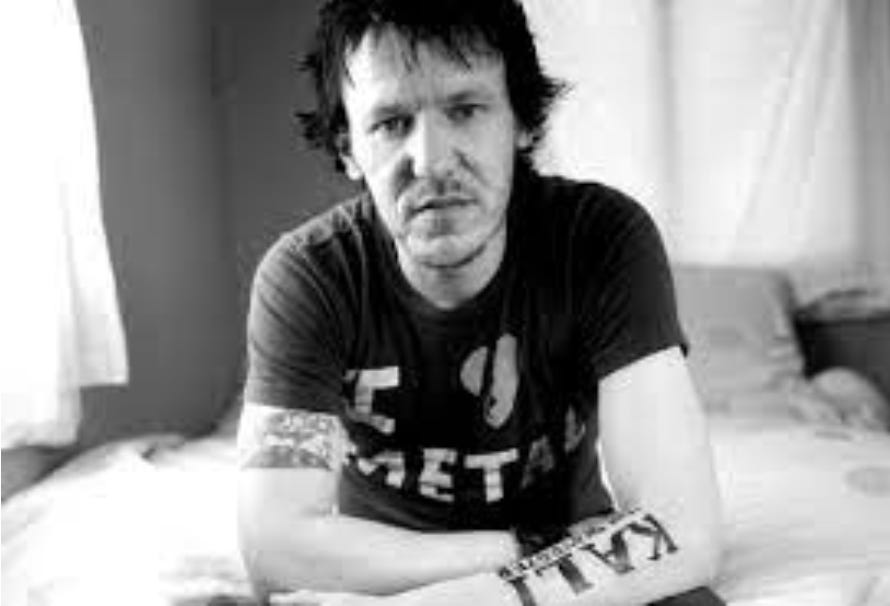

Elliott Smith, who died in 2003, is sometimes remembered as the patron saint of paralyzing sadness, but this typecasting obscures a less remembered, more exuberant side of his personality, one that did Buster Keaton pratfalls and a credible moonwalk,2 spot-on impressions of Mick Jagger dancing and Stevie Wonder driving, the Elliott Smith who laughed and turned from happy to sad and back again as he drank with you and shared his incandescent emotional presence until dawn, or until the bars in Manhattan closed at four, at which time he would descend into the subway tunnels like a drunken Persephone and walk them all the way back under the river to Brooklyn, never finding the settlements he had read about in The Mole People by Jennifer Toth.3

Repeating images—roses, ice, ricochets, and snow angels—move through Smith’s songs like nested circles expanding on the surface of water and one of his hidden exuberances—the pratfall—is the initial and outermost circle.

Ashley Welch, Smith’s sister, told Autumn de Wilde, Smith’s friend, that once, while they were waiting for de Wilde in a bar, she and her brother Elliott decided to go kill time in a parking lot:

ASHLEY: So we went across the street, and we practiced pratfalls for like an hour. I was terrible, but he was so good. He said Sean Croghan and he used to do them and they wouldn’t stop until someone injured themselves .... We were tripping over those, you know, parking stops and curbs and cracks in the sidewalk and stumps, stubbing our toes. He was so good, I couldn’t believe it. We were falling down laughing.

AUTUMN: I think now I have a memory of him doing it on Sunset Boulevard while we were shooting. I remember him showing off one pratfall where he pretended he was passing out and falling flat on his face.4

Falling initially appears on Smith’s first album in the form of “a stutter step you hear when you’re falling down” and a character who “got knocked down leaving like you ran into a clothesline.”

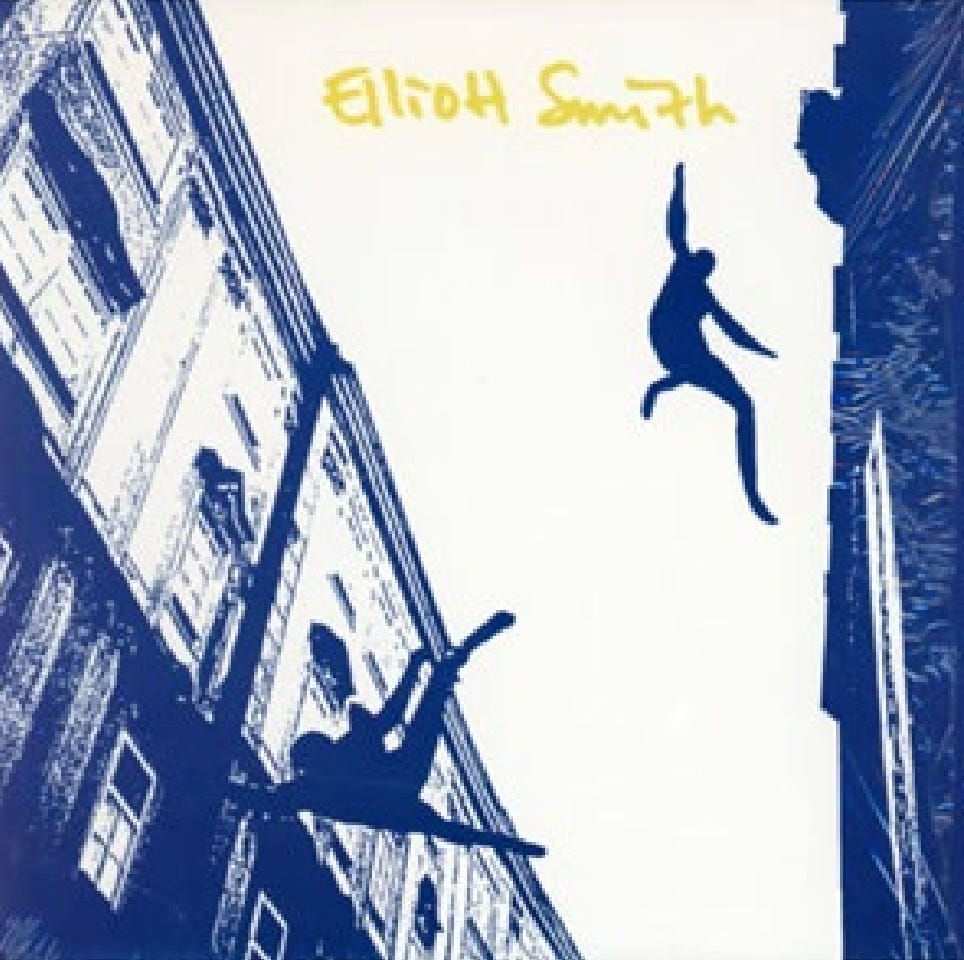

The cover of his self-titled second album depicts falling bodies, and one of its tracks reimagines a traditional song about the daughter of a “forty-niner” miner—who tripped, while wearing “herring boxes without topses” and fell to her death in the foaming brine of the South Fork River,5 while the protagonist of the album’s best known song is “falling out” of a bus at the corner of 6th and Powell in Portland.

The narrator of Division Day, an outtake from Smith’s third album, stands on a bridge and imagines—over one of Smith’s brightest and most mesmerizing melodies and the Willamette River—“flying to fall away from you all.” Two of Smith’s songs from that era are titled like pratfall instruction booklets, How to Take a Fall and Taking a Fall. On the former, the narrator associates falling with an escape from the ghosts of childhood trauma:

Make me a present, make it something sweet Small enough to go unnoticed and big enough to compete With the massive past that keeps blocking up my street Looking for a new contender to disassemble

Taking a Fall focuses on a frayed relationship. One view of the song is that it measures the cost in isolation of fighting an old problem of childhood trauma with a new problem of drug dependence:

Took it like medicine, horrible, in a hurry Lots of plans go awry, nothing’s wrong, I won’t worry But I rolled for a dollar on your advice And I lost you bad 'cause that's the luck of the dice Taking a fall You don't know who to call Well you don’t know who, do you? Taking a fall

A movie playing at a neighbor’s place on the Oscar nominated version of Miss Misery reflects the narrator’s ambivalence about following his own instructions:

Next door, the TV’s flashing blue frames on the wall It’s a comedy of errors you see, it’s about taking a fall To vanish into oblivion, it’s easy to do And I tried to leave, but you know me, I come back when you want me to

Buster Keaton is the greatest faller in human history. He got his first name at 18 months when he fell down a flight of stairs and a vaudeville friend of his parents, who became Harry Houdini in Keaton’s increasingly apocryphal tellings, scooped up the tiny, stone-faced boy and exclaimed: “What a buster!”

By the age of three, Keaton was in a wildly popular traveling act with his parents: his mom Myra would play saxophone while his dad grabbed furious and red-faced for a luggage handle sewn into the back of the child’s shirt to generate greater torque, so as to better throw Buster all over the stage and off it, into the orchestra and into the audience.

The original boy-who-lived would later say that he learned not to laugh during pantomimed abuses because the audience laughed less if he appeared to be enjoying it. Keaton knew that as he fell, audience engagement rose like an elevator counterweight.

He took this secret to his movies, where it became a foundational beam of Hollywood,6 and where his face is a mask of passive detachment while his body absorbs, parries, and reconstitutes with dazzling grace the dangers falling on him in sheets, unceasing weather that he learned to inflict upon himself, taking over the role from his menacing father of the conjurer of his own harm.

My book about Elliott Smith tracks, in the biographical record and in the narrative told across the songs, a common nightmare of human history: abuse by a stepfather, who the songs refer to as Some Crazy Fucker from the South, Mr. Man with Impossible Plans, The Bad Dream Fucker, The Boss,7 The Angry Mean Baby, Some Monster Offscreen, Sgt. Rock, Some Dude with a Stilted Attitude, The General, The Clown,8 or, just—on three songs Smith did not put out on albums—Charlie.9

The passive detachment of Keaton’s face is paralleled in Smith’s vocal delivery, as he never reaches for sympathy, but instead sings everything—even the most blood curdling visions of hell—in the same even keeled middle range. The book describes how the narrator of the songs became the conjurer of his own harm and plays at launching himself into oblivion. For this tragic movement, Smith chose the comic image of Keaton’s pratfall.

This maneuver, this merger of the poles of existence, is tied to the goddess principle, the first clues of which appear in the form of “the mighty mother with her hundred arms” on No Name #1 from Roman Candle, and from a prayer arising from that album’s Last Call:

Church bells and now I'm awake And I guess it must be some kind of holiday I can’t seem to join in the celebration But I’ll go to the service And I’ll go to pray And I’ll sing the praises of my maker’s name Like I was as good as she made me

Half of the Goddess principle is the sleep of death, and Last Call ends with eight repetitions of “I wanted her to tell me that she would never wake me.” Toward the end of his life, Smith took to scrawling Kali the Destroyer, the Hindu mother goddess, on his left arm.

Even the Ferdinand the Bull tattoo on his right arm bore a connection to goddesses, through the animal sacrifices made to them, as Smith associated the tattoo with bullfighting, a modern grandson of such ancient rituals.10

To understand Smith’s use of a comic image to dramatize catastrophe, we should remember the structural essence of comedy is a happy ending and that in goddess mythology death is bent into a circular relationship with rebirth.

Elliott Smith is full of elliptical references to Persephone who spends six months in the underworld each year with her dirty uncle Hades and six months above ground blooming with life. Coming Up Roses embodies the circularity of Persephone, as the hero’s fall yields a rose-field of enduringly beautiful songs:

You’re buried below And you’re coming up roses

XO’s Baby Britain sees “the ocean fall and rise” and the circularity of the goddess principle is the center of Smith’s central image of falling. The comedy of the image is rooted in the idea that we can rise as we fall. On the late True Love, the wish for death murmured through the book of Elliott Smith is also a wish to rise into the presence of God:

Take me up, my Lord Take me up today Take me out of this place Take me up with you today

The vertical whirlpool of a simultaneous fall and rise carries us to the eighteenth century theologian, Søren Kierkegaard, whose first book11 has the same name as Smith’s third album. After the release of Either/Or, Smith’s solo career was opening into a full, blood-red bloom while his band, Heatmiser, was tripping into pale obsolescence.12

At one of Heatmiser’s last shows in 1997, Smith’s bandmate Sam Coomes introduced him with affectionate ball-busting as “Søren Kierkegaard, on guitar.” The hidden overlap in the life and work Kierkegaard and Smith is deep and wide, but can be distilled down to the single most influential sentence in all of Kierkegaard’s many books.

In 1843, Kierkegaard, writing under the stage name Johannes de Silentio, or Johnny Silence, invented the concept of a leap of faith, writing that the greatest move that the Knight of Faith ever pulled was “to be able to fall down in such a way that at the same second it looks as if he were standing and walking to transform the leap of life into a walk, absolutely to express the sublime and the pedestrian—that only these knights can do—and this is the one and only prodigy.”13

The narrator and dramatic personae in the songs of Elliott Smith suffer falls—child abuse, the isolation and decay of drug dependance, the failure of love14 —but the musical structure of the songs welds a lift into each fall. The marvel of this achievement is still not fully appreciated, and Smith was equipped to accomplish it with a genius for melody and harmonic invention that rendered compositions that are “warm but precise,”15 “a magic trick,” and “a kind of a watch-work organized beauty.”16

His chord changes, the internal motion of the chords, were always logical in a very beautiful way. That’s what makes Bach tick. That’s what makes the best Beatles stuff tick ... He really genuinely loved the emotions that were generated by chord changes. He understood it better than anyone I have ever met, quite honestly, by a long shot. It’s not something that we used to talk about in this way, or that many people in our generation were particularly interested in. People that were interested in chord changes ... were only interested in making it sound like whatever older type of music they liked. It’s like a borrowed harmonic language, as opposed to finding some sort of new beauty, even if stylistically you are presenting things with old-fashioned instruments. Like ‘Independence Day’ or something, which has a very interesting, beautiful natural motion.17

Independence Day—a wish for a friend dramatized in the fall of a caterpillar and the rise of a butterfly—opens a door into the spiritual quality that takes increasing prominence in Smith’s later work. As that quality relates to pratfalls, falling is counterpoised with arising and standing (“Took a long time to stand, took an hour to fall”), and standing is linked to love (“But now I feel changed around and instead of falling down/I’m standing up, the morning after”). In the song Either/Or—which, in an irony repeated on Figure 8, does not appear on the album Either/Or—Smith sings of “an endless symbolic war.” In Kierkegaard’s Either/Or, a tension between the aesthetic and the ethical modes of life creates a path toward a third way: the spiritual. On Smith’s songs, the tension between opposing forces—the rise welded into the fall—likewise creates conditions for transcendence. When the body of an actor careens into death in a car accident on the last album Smith released, Figure 8, his spirit rises in its essential form of loving kindness, and the narrator—looking forward in time—merges with him on the flattened circle of that record:

What I used to be Will pass away And then you’ll see That all I want now is happiness for you and me

Elliott Smith believed that “it’s our imagination that’s the divine force.”19 Just as Kierkegaard’s Knight of Faith rises up into the eternal during a single moment of a finite life, Smith—by welding the lift into the fall—created songs that are fragments of eternity, durable expressions of loving kindness and the divine possibilities of human art. This leaning out toward the eternal is why he identified with skaters cutting figure eights into ice. “We have,” he said, “the impression that nothing else matters to them, that they are caught in a sort of perpetual movement that nothing can disturb. They have a taste for something eternal, mystical, a sort of quest for the absolute that I find very moving.”20

In the Elliott Smith cinematic universe, the dominant shorthand for the greatest psychic pain, the farthest distance from love, and the deepest hell are: ice, cold, and snow. On Angel in the Snow, the narrator imagines falling to lay in perpetuity beside the listener, asking three times: “Don’t you know that I love you?”

The spiritual element of Smith’s work—figure eights he left on the ice and angels flapping warmth always into the snow of human suffering—reaches a high water mark on a song that cannot be found on any album, or even as a standalone on Youtube, Spotify, or any of the other hoarding, algorithmic behemoths. One of the greatest songs ever written, as it stands, can only be found on the Vimeo account of a man named Ben Wilbur, where it has 11 likes and two comments, one about tears, one about copyrights. On the hard to find masterpiece, the fall goes all the way down into the dirt:

You took a fall and I followed down as far as I could go Grand mal, it’s all over now, buried back below

The song performs an imaginative miracle where the traumas of the singer converge into the traumas of the listener. The singer calls up the image of his own eyes, his mirror eyes, that have seen the kind of grand mal suffering that he wants to save the listener from now. And all he has to offer is the only thing that rose through all of his many falls:

“Don’t forget,” he sings, “how much I love you.”

ENDNOTES

Pipersville Pheasant Press does not, strictly speaking, exist. If Eckert cannot find a publisher for the book, he plans to publish it himself in the new year, at which time, the Pheasant—as it’s affectionately known—will cross the boarder-line between the fanciful and the vendible.

Moonwalking moment as well as studio footage of Smith’s cover of Because by The Beatles.

Toth, Jennifer. The Mole People: life in the tunnels beneath New York City. Chicago Review Press: 1993.

de Wilde, Autumn. Elliott Smith (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2007). Pages 152, 72.

In May 1928, Keaton released Steamboat Bill, Jr., which inspired Steamboat Willie, the Walt Disney short that opened six months later, birthing an empire. Images and scenes from Keaton’s movies have, moreover, been endlessly copied and cap-tipped throughout the history of Hollywood.

See also: Christian Brothers, New Monkey, and Son of Sam (As to goddesses, Son of Sam tries to make one out of Shiva, the Hindu God of destruction, whom Smith misgenders, possibly under the influence of the Final Fantasy video game series. See Hess, Nick. “Elliott Smith, Shiva, and Final Fantasy Walk Into a Bar.” Thought Catalog. November 21, 2012.)

See also: No Confidence Man and Flowers for Charlie.

JJ Gonson, who was dating Smith at the time he got the tattoo said Smith “[s]omehow missed the point of the children’s story, which I’m not sure he ever read and which is about pacifism.” Ferdinand the Bull arose on Smith’s arm not as straightforward ode to peace but from what Gonson called his “truly perverse fascination with bullfighting.” Nugent, Ben. Elliott Smith and the Big Nothing. Cambridge: De Capo Press, 2004. Page 61-62.

Kierkegaard, Søren. Either/Or: A Fragment of Life.

Heatmiser has had a strong afterlife and remains influential. See My Favorite Elliott Smith Song: Sadie Dupuis.

Kierkegaard, Søren. Fear and Trembling. A&D Books. Pages 32-33.

Pratfalls are, of course, perilous. The narrator of Coming Up Roses was wary of his identification with Persephone, and of being the writer/director/actor of his own one-man vaudeville: “The things that you tell yourself,” he sang, “They’ll kill you in time.” And the biographical Smith was, of course, not impervious to falls, including off a cliff behind a cul-de-sac in suburban North Carolina and into some of the foaming brines described in his songs. See Nugent, Benjamin. Elliott Smith and the Big Nothing. Cambridge: De Capo Press, 2004. 126-127.

de Wilde, Autumn. Elliott Smith (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2007). Pages 210-211 (quoting Jon Brion).

Conte, Christopher. Elliott Smith – Le huitième ciel. Les Inrockuptibles, April 18, 2000.